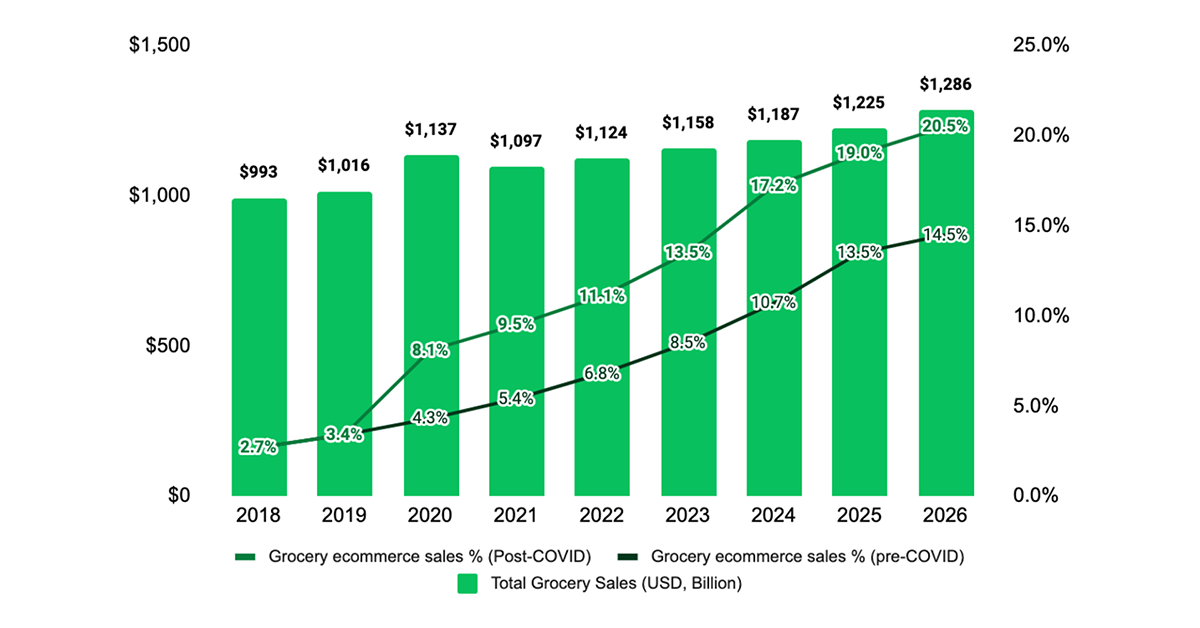

Historically, growth in grocery retailing has always been glacial. As per the Incisiv-Wynshop Digital Grocery Study, the sales growth is 2.7% year over year, on average. In fact, in the last three decades, sales have grown more than 5% YoY, only once in 2011. In 2020, sales more than tripled the average annual growth to 9.5%! The main driver of this growth was attributed to the rise in digital sales, which were up by more than 5x over 2019.

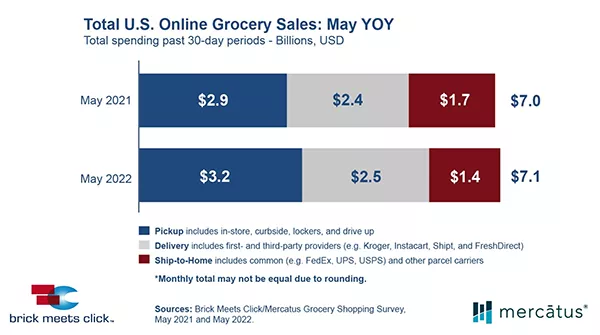

As has been well documented, digital’s unexpected growth came as a result of the global pandemic that effectively shut down the world. However, people still needed groceries and other essentials, but with lockdowns and “shelter in place” orders, the only way to shop was online. This sped up the adoption of digital by new customers and forced grocery retailers to quickly implement and expand new capabilities (e.g third-party partnerships, curbside delivery, etc.).

This growth, however, has come at the cost of profitability. With digital projected to rise to 20% of overall sales by 2025, grocers will need to focus their attention on improving their digital execution.

Profitability of Digital Orders Remains Low

While there was an increase in online orders, whether in terms of average basket size or volume, most grocery stores, particularly those with less than a billion dollars in revenue, failed to profit. As a result, it’s unsurprising that 86 percent of grocery retailers are dissatisfied with the profitability of their online operations. The average gross margin for digital orders was barely 9% in 2020, according to the Incisiv-Wynshop Digital Grocery Study, and many retailers even lost money on their online orders.

Grocery retailing is difficult. It’s a complex business with low growth and meager margins. While the quick digital growth of 2020 was great for revenue (+9.5 percent), merchants lost 70 percent of their profit on online orders and became a step distant from their customers. According to this aforementioned analysis, grocery retailers will lose $14 million in gross margin for every billion dollars in sales in 2025, if the present sales and profitability patterns continue.

Digital Operations are Inefficient

In comparison to other retail divisions, grocery retailers’ digital operations were quite undeveloped prior to 2020. In 2020, they were pushed to their breaking point by a 5x increase in demand and the inclusion of additional fulfillment methods (e.g., curbside).

Fortunately, this expansion uncovered execution inefficiencies that are critical to increasing profitability: knowing where the goods are (inventory visibility), picking them efficiently (order picking efficiency), and sending them inexpensively (last-mile delivery).

According to the Incisiv-Wynshop report, order picking efficiency is at the top of the list, with 92 percent of grocery retailers dissatisfied with their order picking efficiency. To reduce fulfillment costs, food retailers will experiment with capabilities such as micro-fulfillment centers, automated picking solutions, and labor models during the next 24 months.

Continue to read the full article on Grocery Doppio.

With online grocery adoption accelerating, automated order picking is essential to e-grocery profitability. The Alphabot® System powers your automated store picking systems, dark stores, or “hub and spoke” distribution model. The Alphabot System will also automate micro-fulfillment center replenishment at less-than-full-case levels, dramatically increasing the number of SKUs each location can support. Learn how the Alphabot System makes e-Grocery micro-fulfillment implementation practical and cost-effective today, while providing a platform for the future.